Jump Training and Monitoring for Triathletes

Concurrent training programs consist of both endurance and resistance training to maximize all aspects of performance. For endurance athletes, research strongly supports the benefits of adding strength and power training to programs. These benefits include:

improved movement efficiency

increased speed via improved lactate thresholds

reduced risk of overuse injuries

The key to unlocking these benefits is proper implementation, involving:choosing the right technique strategy to play to the athlete’s strengths

choosing the highest impact accessory exercises to address potential weaknesses

applying the right training dosage - enough to create training adaptations but not so much that injury risk increases

Load management strategies are especially important for multi-sport athletes like triathletes.

Using Biomechanics to Create a Training Effect

Triathletes are unique because they compete in 3 different activities, each of which requires its own respective training adaptations.

For example, cyclists have some of the most enormous quads in the world! These athletes devote considerable time to strength and power training in the gym to complement their track training.

This next image depicts the contributions of different muscle groups to pedal stroke power. The thickness of the curve at the bottom of the image shows the relative contribution and timing of each muscle’s involvement. The quadriceps play a critical role in high power production over a short section of the pedal stroke. The glutes and calves then follow.

In running, however, we don’t generally see any particularly oversized muscle groups, but the quadriceps still play an essential role in both absorbing impact and forward propulsion. The calves also assist in impact absorption and propulsion, but in different ways depending on foot strike patterns.

OK, so why incorporate jumps into Triathlon training?

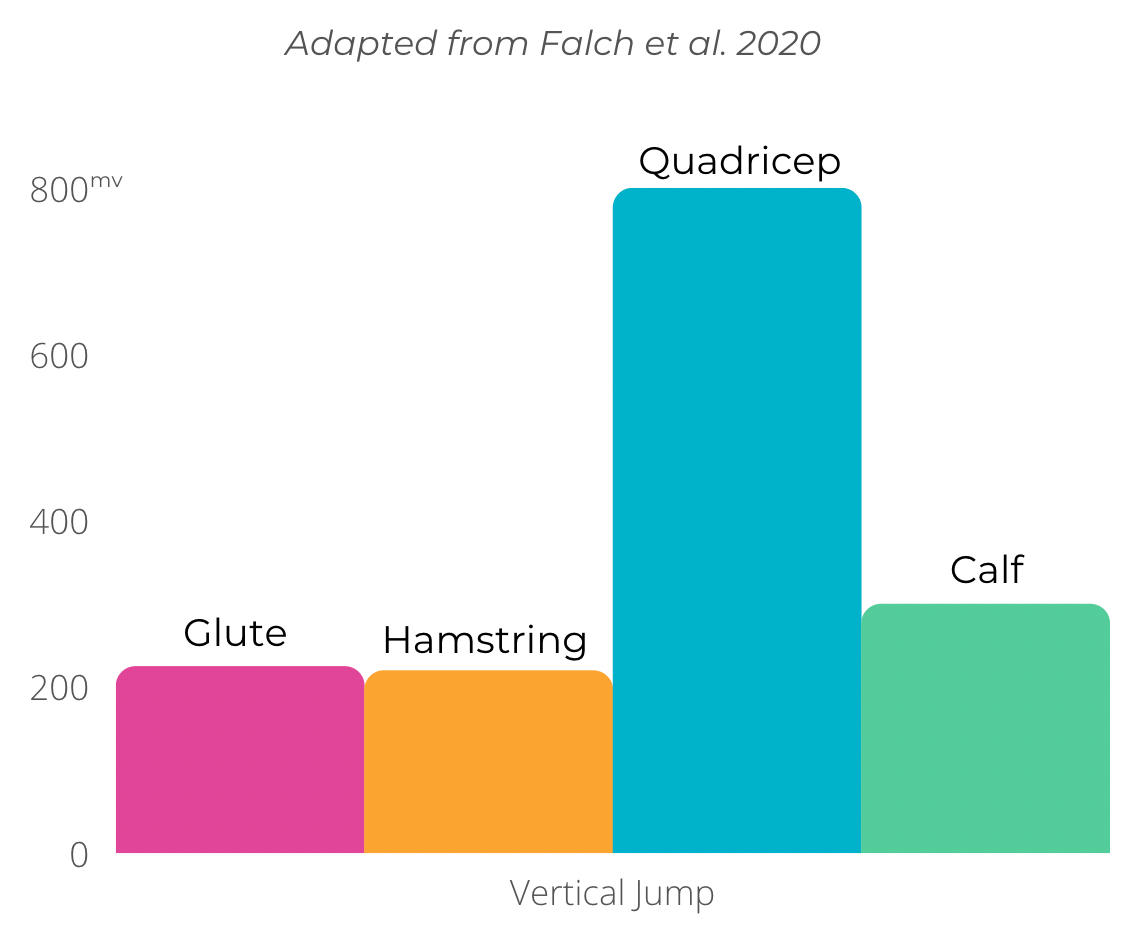

First, check out how muscles contribute during vertical jumping in the figure below. It looks pretty proportionately similar to cycling, right?! The quadriceps are the primary muscle group used in vertical jumping. The glutes and hamstrings are the primary muscle groups used in horizontal jumping. The calves control and fine-tune the direction of push-off in both vertical and horizontal jumping.

Now watch the slow-motion videos of jumping, cycling, and running below. In all three cases, the propulsion phase starts by extending the hips first, followed by the knee, then the ankle. This movement strategy transfers and amplifies energy through the lower body as the toes leave the ground and the pedal moves through the 6 o’clock position.

If several jumps were done in a row, the athlete might even jump higher in the consecutive reps due to the “springiness” of the muscles and their tendons. Running and cycling take advantage of this natural springiness in their repetitive movements.

Now let's put the pieces of this jumping puzzle together

Including jumps in your athlete’s triathlon training program can help reinforce more efficient pedalling and running strategies

Jump training targets the quads, hips, and calves, training them to be in the right positions at the right time for both cycling and running. This can help improve performance and reduce injury risk in both activities

Box jumps, weighted squat jumps, and Olympic weightlifting movements are excellent power training exercises that develop muscle strength & explosiveness in these muscles.

Plyometrics that involves either of the following can help improve BOTH cycling & running performance while reducing injury risk:

a) consecutive reps like a cyclic jump, consecutive CMJ, & SLJ RSI as examples or

b) an initial drop from a height & subsequent rebounds like drop jumps or depth jumps

Periodic jump baseline testing can be a powerful monitoring tool to evaluate muscle performance in cyclists and runners.